Correcting user error

By Richard Hawkins, MACS Contributor

Correcting user error. This is the second part of a two part blog. Read part one here.

When I had initially spoken with Joe on the phone, he was pretty upset about his refrigerant recovery (R/R) machine not working. Upon my arrival at his shop, he was a bit more cordial, but he did not have much time to spend with me because he was busy.

As a result, after he provided a bit of information, he said something like: “I have several jobs I need to get completed, so I can’t hang out back here with you while you’re checking the machine out. There’s my toolbox over there. Feel free to use any of my tools. I’ll be over in the second bay working on that old piece of junk truck that a customer brought to me to get ready for an inspection. If you need anything, just holler.”

As mentioned in last week’s article, the first thing I did with the machine was check the pressure of the refrigerant in the tank. It was extremely high (well over 400 PSI) indicating there was a refrigerant contamination problem. Rather than try to remedy that right away, I was more concerned about getting the machine into operation as soon as possible. To accomplish this an empty tank was installed, and the machine turned on and the refrigerant recovery process was continued on the van the machine was connected to. I let Joe know (and he was very happy) and then turned my attention toward the refrigerant tank which I had removed from the machine.

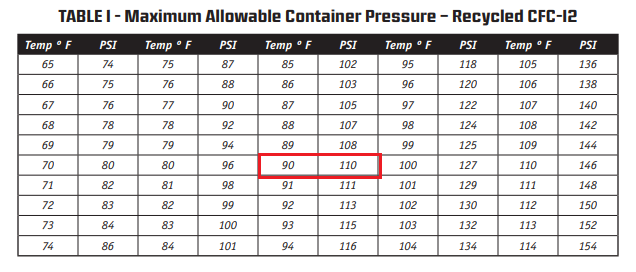

The next order of business was to try to purge the tank to get the pressure down into an acceptable range and that was where things got interesting. This was 1991 and we were dealing with R-12. It was early-summer, and I don’t recall what the actual ambient temperature was that day, but for purposes of illustration we will use 90°F. At 90°F, the maximum allowable container pressure for R-12 is 110 PSI. Please see the chart in picture #1.

Picture #1. This is a chart from the MACS Section 609 Certification Training Manual.

I proceeded to open the purge valve and slowly purge the tank. With the tank pressure being so high, I knew it was going to take a lot more time than usual and I would need to purge and check the pressure multiple times. After about 2 hours of purging and checking and letting the tank temperature stabilize the pressure was still above 200 PSI. This was over 90 PSI higher than what it was supposed to be and an indication this was no normal case of air contamination.

At that point, I called one of the engineers who had helped develop the machine to get his input. He said he felt the refrigerant was cross contaminated with another refrigerant and some air too. That was indicated by the initial extreme high pressure and the fact that the pressure had dropped significantly after the purging (which was a result of the air being eliminated).

The most likely refrigerant which was causing the cross contamination was R-22. This was because the price of R-12 was beginning to escalate. Also, R-134a and all the blends that came into the marketplace had not been introduced at that time and R-22 was very inexpensive. I had read about shops putting R-22 in mobile A/C systems and had spoken to someone a few weeks earlier who told me he had done it. The engineer suggested that we try purging more of the refrigerant but he didn’t think the pressure was going to get much below the 200 PSI range.

Quite a bit of time had elapsed, and Joe had caught up some and had some time to talk. I explained what had transpired thus far and asked him when the last time was he had performed a non-condensable gases check. The conversation went something like this:

Joe: What do you mean?

Me: When you attended the certification clinic there was a procedure covered in it for checking for the presence of non condensable gases (that’s the term they use for air). I also covered the procedure the day I came over and set the machine up and it is covered in the operator’s manual. How often do you perform that procedure?

Joe: (Looking a little embarrassed.) I’ll be honest with you. I haven’t ever done that. I just totally forgot about it.

Me: That’s what I thought. A non-condensable gas check would have alerted you about a problem long before you experienced the issue of the machine not being able to recover refrigerant.

Joe: I’ll be sure to remember to do it in the future.

I had Joe do some more purging on the tank of recovered refrigerant over the next several days, but the tank pressure never got anywhere close to the maximum pressure indicated on the chart which confirmed that refrigerant was cross contaminated.

Every time I saw Joe after that, before saying hello he would always smile and say: ” I’ve been doing my non-condensable gas check.”

This was my first experience dealing with contaminated refrigerant in a recovery/recycling machine and it etched three things in my mind.

1. The need for frequent non-condensable gas checks.

2. How much of a potential problem refrigerant cross contamination could be.

3. The need for refrigerant identifiers (which had not been introduced to the market at that time).

MACS blogs are just a sample of the technical information available from our community.

Join MACS today as a member to take advantage of all the technical information, MACS has to offer.

Leave a Reply